Air Conditioning is a Bridge to Climate Adaptation and Community Schools

Air conditioning in schools is a seemingly endless issue. The introduction in 1998 of provincial per-pupil funding for Ontario school boards transferred ownership of the controversy to the ministry of education; with trustees and parents suggesting, requesting, proposing and now demanding the necessary funding to upgrade all schools with air conditioning.

It begs to be asked, why is this even controversial? If I go to a grocery store, bank, library, museum, or any public building, it’s air conditioned. But not schools. We say we love our kids, teachers and support workers. Just not enough to ensure they have appropriate working conditions. Yes, when students are in school, they are working - just like adults.

Why won’t the provincial government ensure that all of our public schools are air conditioned? What’s the real problem? Of course, money is always deemed to be in short supply. But something larger is at play. The air conditioning controversy demonstrates how entrenched our public education systems are.

Schools close for the summer. It’s always been that way, so why do they need to be air conditioned? Sure, mother nature imposes a few uncomfortably hot days every school year. But we all lived with that when we were students. We prevailed until the doors of the school closed at the end of June and we all merrily headed off for summer break, hopefully at a cottage or near a beach.

The outdated narrative about schools and air conditioning is now out of sync with reality. Mother nature no longer dictates an occasional number of extreme heat days. It’s now a human driven and increasingly dangerous health issue. This fact is acknowledged by the Ontario government’s own 2023 Ontario Provincial Climate Change Impact Assessment Technical Report.

“Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our time. Rising atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases are altering the earth’s climate, driving increases in global average temperatures and variability and extremes of weather. These changes are causing unprecedented impacts, transforming ecosystem structure and function, damaging infrastructure, disrupting business operations, and imposing harm to human health and wellbeing. Physical climate impacts and risks to human, natural and built systems in Ontario are driven by average annual warming temperature and extreme heat, drought, changes to intensity and frequency of precipitation and other climate variables.” (p.xiii)

Furthermore, “Extreme Hot Days, or the average number of days where mean air temperatures exceed 30°C, are expected to rise significantly across Ontario.” (p.42) (It is interesting to note that the 19 Ontario ministries assembled for an Impact Assessment Inter-Ministry Committee (IAIC) to assist the development of the technical report did not include the ministry of education.)

The scientific reality cannot be denied. Greenhouse gas emissions are not being reduced quickly enough to reverse the impacts of the climate crisis. We are running out of time. Our continued delay will have increasingly harmful public health consequences. That’s why adaptation must now be prioritized, with sustainability, by the provincial (and federal) governments. This will be challenging for a provincial government that has been indifferent in its funding support to school districts.

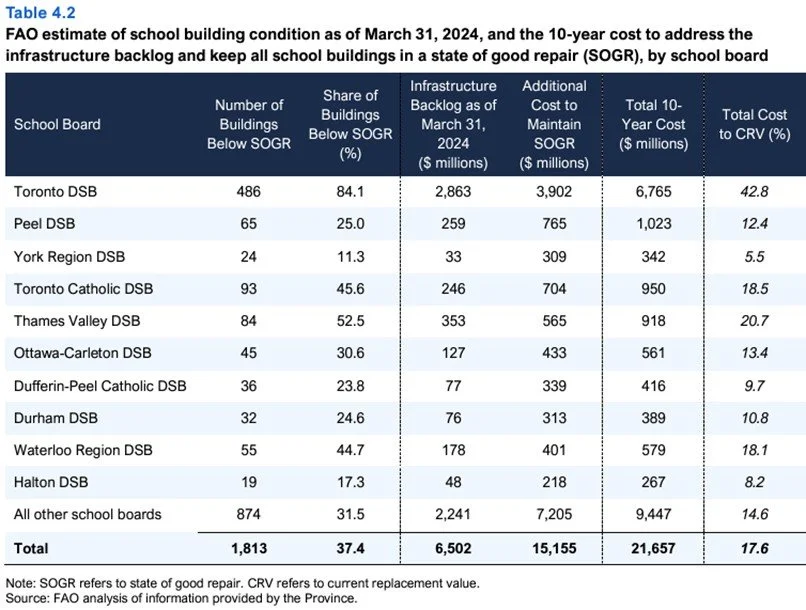

A frustrating lack of accountability to the societal advantages of a strong system of public education is evident from the substantive abandonment of provincial funding for school boards. This isn’t a political statement. It’s a fact illustrated, among other things, in the following table provided by the Ontario Government’s own Financial Accountability Office (FAO) in its 2024 School Building Condition, Student Capacity and Capital Budgeting Report.

It can be seen that 1,813, or 37.4% of Ontario’s school buildings are below a state of good repair (SOGR), with this percentage exceeding 40% to 50% for some school boards. Remarkably, 84.1% of Toronto District School Board (TDSB) school buildings are below a state of good repair.

But the narrative about the gap in provincial funding for school buildings doesn’t end there. That's because maintaining a state of good repair also needs to account for the climate crisis. This fact is authorized by the FAO via the Costing Climate Change Impacts to Public Infrastructure (CIPI) report commissioned by the provincial government in 2023. “The FAO projects that in the absence of adaptation, these changing climate hazards will add $4.1 billion per year on average to the cost of maintaining the $708 billion portfolio of existing public infrastructure in a medium emissions scenario. This represents a 16 per cent increase in infrastructure costs relative to a stable climate base case.” (p.1) In other words, an immediate funding increase of 16% is required to simply maintain 84.1% of TDSB schools, and 37.4% of Ontario school overall, below a state of good repair.

The Ontario ministry of education has a problem. Our communities, witnessing the new normal of the climate crisis, are now challenging generational interpretations about what public schools are and could be. Public schools need to be fully integrated with community needs and services at large. Provincial governments can be expected to delay this necessary effort because the operational deficit of school districts is so prominent. A fundamental provincial government commitment to air conditioning for all schools will open the door to a wide range of adaptation needs – not just for facility upgrades, but for staffing and integrated support services.

If all schools become air conditioned, shouldn’t they be available for general community heat relief? How would that be supervised? Could a curricular connection be made for students throughout each summer? How would that be staffed? What about air quality control in response to wildfire smoke? What about facility upgrades to address flooding? Can schools be readily available for community emergency response? Can schools become more integrated with community services such as mental health, connected as it is with child and adolescent anxiety due to the climate crisis? What does this type of school actually look like?

Community and educational leaders must resist the urge to interpret the climate crisis as peripheral to current school district and school operations. The climate crisis has become the key driver of system operations. This is no longer a futuristic consideration. The science tells us it is happening now, whether we want to admit it or not.

Phil Dawes

July 7, 2025